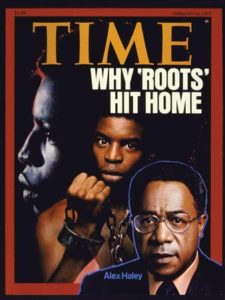

In my last post, I called out Pulitzer Prize winner Alex Haley and his 1966 interview in which he was able to capture the time and place through not only his first questions but his 547-word narrative introduction to "the fanatical führer of the American Nazi Party," partially quoted below. The final Q&A itself was comprised of 117 questions and weighed in 11,712 words.

Warned about my Negritude, he registered no surprise nor did he smile, speak or offer to shake hands. Instead, after surveying me up and down for a long moment, he motioned me peremptorily to a seat, then sat down himself in a nearby easy chair and watched silently while I set up my tape machine. Rockwell already had one of his own, I noticed, spinning on a nearby table. Then, with the burly guard standing at attention about halfway between us, he took out a pearl-handled revolver, placed it pointedly on the arm of his chair, sat back and spoke for the first time: "I'm ready if you are." Without any further pleasantries, I turned on my machine.

Nevermind the interview; the introduction alone is longer than many articles today. Wow!

In this post, I discuss the state of the interview, specifically the longform interview, and why I think the conversations we are having with celebrities are getting shorter.

I believe there are three main reasons:

- there is less space because there is more content overall;

- there is less money coming into publishers, so there is less money going out to writers; and

- many publishers and editors thumb their noses at the Q&A.

Less space

Many publishers believe readers' attention spans are dwindling, if they are reading at all.

On last night's controversial episode of Real Time with Bill Maher, former Google ethicist Tristan Harris, promoting his nonprofit Time Well Spent, argued that technology companies like Facebook hack the consumer brain to stake their claims in "the attention economy." The consequences of which include a trend toward people distributing more and more of their attention across many interests. A number of other similarly incentivized experts agree.

"The moral rot in this country began when corporate America decided it wasn't enough to just successfully sell your product; people needed to be addicted to it."

—Bill Maher, Real Time with Bill Maher, June 2, 2017

For publishers, this business-driven assumption—that is, they see the money that rolls into those technology companies and want their piece—fundamentally reshapes editorial agendas, turning sometimes once-honored publications into little more than sensationalist Tumblr feeds. In those feeds, there is little space for longform, investigative content.

If you have read my work, you might be thinking, "But, Morgan, you do realize you have published some very, very long interviews, right?" I do realize that. I have many interviews between 30,000 and 80,000 words, or 20 to 50 times the lengths of most Q&As, but I have a certain freedom with space and time as an author that I do not have as a features writer.

When I have worked as a features writer, editors have given me length targets of between 1,500 and 3,000 words, of which the latter I have been told would be on the long side. These are editors, by the way, of online publications where space is not limited by advertising dimensions and printing costs. This suffocating spotlight for exploring subjects is only smaller in print. I was once asked by a magazine editor if I would work with just 400 words for an entire interview.

I do not know, personally, what type of interview I could produce in 400 words, and I have just enough self-respect to not find out! Interviews that readers will remember an hour, a week, or a year later absolutely need room to breathe, and if the publication cannot provide that space, they cannot secure the kind of profound, humanist content that interviews offer.

Less money

Freelance writers in media are paid by the word or at very humble fixed rates. How much time can a writer reasonably spend on an 400-word article worth 10 cents per word? Some editors even have the audacity to offer only $100 (or less!) for a 3,000-word article.

Successful writers have publications aplenty listed in their biographies, and not because they are prolific—a common adornment for writers opposite their natural state. They must split their time and focus between assignments for different outlets to eek out some semblance of a living wage.

I would love to complain freelancers are not paid what they are worth, and that is generally true, but let us be honest about the work. The content they are asked to produce to generate a few thousand views will not win any awards or turn around failing publishers.

And what content is that? Shortform articles filling time between the odd feature, news about nothing devoid of expert analysis, and games of 10 or 20 questions teasing out not any unrealized truths or accountability but rather marketing messages designed to titillate sales. Trade journalism is often made an extension of the corporate subjects it should investigate, reliant on the buzz-building expertise of more highly paid j-school graduates to drive traffic.

In their struggle to reduce costs and keep the lights on, publishers ultimately ask editors, not explicitly but through fiscal responsibility, to produce content at a minimum level of quality that won't push readers away. But that minimum level of quality also won't attract new readers.

Publishing is a business, but yet another where those in control of the purse strings are so averse to risk they seal their fates by not investing in content that will grow their business.

Less respect

Despite my experience as an interviewer, I do not think so highly of my work I am convinced I can do no more to develop my craft. In 2013, I sought out the best interviewers by reputation for their advice, and I chanced upon a writer named Lawrence Grobel, and asked whether he was aware of any "master classes in interviewing." He introduced me to his book, The Art of the Interview.

In that book, Larry asked his colleagues what they thought about writing profiles versus writing interviews. The answers are revealing about where the Q&A stands.

Some editors think narrative writing requires more skill than interviewing.

"[Q&As] are easier to execute and harder to screw up than profiles."

—Kevin Cook, sports editor and author of Tommy's Honor

Some editors think interviewers are less-than-writers.

"I think [the Q&A] is an underused and generally undervalued form. In fact, I once had an editor—who will remain nameless—tell me I should be paid less than the standard rate by his publications 'because Q&As aren't writing.'"

—Kristine McKenna, music critic and author of Book of Changes

Some editors think so little of interviews that "anyone can do them."

"I believe many editors think of [Q&As] as stories on the cheap. They also live under the illusion that anyone can do them—including sometimes themselves."

—Claudia Dreifus, author of Scientific Conversations and Interview

It is not so surprising then that longform interviews seem to be on the way out. I have observed editors and readers alike calling profiles "interviews," and online publications tagging their profiles as "interviews" to aid those seeking profiles find what they believe to be otherwise. Some readers and reviewers have even expressed confusion about the question-answer structure of my interviews, as though this time-honored format was a peculiar stylistic choice.

The profile abounds, but the profile speaks more to the writer than the actual subject. The profile, like the best documentaries, has a perspective. The voice of the subject is drowned out by the writer's own voice, reinterpreting the subject through the lens of inexperience.

"I get sick of how a lot of them [critics] write whole columns and pages of big words and still ain't saying nothing. If you have spent your life getting to know your business and the other cats in it, and what they are doing, then you know if a critic knows what he's talking about. Most of the time they don't."

—Miles Davis, the jazz legend in the first Playboy interview, September 1962

As one of the last bastions of longform content, the profile is a poor substitute for what we gain from hearing directly from astronauts, business leaders, sports figures, and other celebrities.

In a protest of sorts, I have taken to describing interviews as profiles in conversation, unvarnished explorations of human stories. The best interviews offer readers a journey into the hearts and minds of individuals, and allow readers to judge what they discover without the writer's commentary. But I will leave the interview's defense to this Grammy Award winner:

"Q&As allow the subject to speak in depth and in his or her own words. They retain the voice of the subject. There's more. Good Q&As ask the questions that readers would want to ask and in addition the ones that most readers would never think of. It's a very satisfying dynamic when it’s done well. […] Q&As are satisfying in another way. After reading a good Q&A, we feel as if we participated in an engaging conversation—entertaining, instructive, or both."

—David Sheff, author of the #1 New York Times Best Seller Beautiful Boy

Conclusion

With less space, less money, and less respect for the craft, interviews, if editors deem them worth conducting, are brief and quick. A friend and former CNN bureau chief told me he accumulated tens of thousands of interviews in his career. Broadcast interviews range between a few seconds to a few minutes long, and aim to extract juicy sound bites that can be replayed for audiences 24/7. Honestly, that is not too different from the 10/20 Questions interview.

It is a rare thing in this shortform media environment that a writer would, for example, spend ten days on a private island with Marlon Brando, as Grobel once did. Instead, interviews are 10-minute phone conversations, or more frequently, the product of what are effectively e-mailed surveys. The opportunity to capture the time and place of the conversation is missed, and so too the means to establish why having that conversation was important then and there.

Are these challenges insurmountable? What can we do? As readers, we must demand, from the publications that receive our attention, content that provokes criticism, inspires us to act, and engages us more deeply than they believe us capable. As writers, we need celebrities to be partners in our collective artistic endeavor; they need to treat the interview as an artform as they would their own works, and not just as a platform for promoting those works. And, as editors, we need publishers to recognize that running a publishing company like a technology company is not the path to success but the road to obsolescence.